FAQs

-

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a progressive neurological disorder that affects motor neurons—the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord responsible for controlling voluntary muscle movement. As these neurons degenerate and die, the brain loses its ability to initiate and control muscle movement, leading to muscle weakness, paralysis, and eventually respiratory failure.

-

The most common initial symptom is a gradual onset of progressive muscle weakness, which is generally painless. Other early signs may include muscle twitching (fasciculations), cramping, stiffness, slurred speech, difficulty swallowing, or trouble walking. Symptoms typically start in the limbs but can begin in the muscles that control speech and swallowing. As the disease progresses, it affects more muscle groups, leading to severe disability.

-

In most cases, the exact cause of ALS is unknown (sporadic ALS). However, about 5-10% of cases are inherited (familial ALS), often linked to genetic mutations such as in the SOD1, C9orf72, or TARDBP genes. Environmental factors, like exposure to toxins or heavy physical activity, may play a role, but no single cause has been definitively identified for sporadic cases. Research suggests a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers.

-

There is no single test for ALS. Diagnosis typically involves a thorough neurological exam, electromyography (EMG) to detect electrical activity in muscles, nerve conduction studies, MRI scans to rule out other conditions, and blood/urine tests. It often requires ruling out similar diseases like multiple sclerosis or spinal muscular atrophy. The process can take time, and a second opinion is common.

-

ALS can affect anyone, but it is more common in people aged 40-70, with a slightly higher incidence in men than women. Risk factors include family history (for familial ALS), military service, and possibly athletic involvement or exposure to certain environmental toxins. However, most cases occur without identifiable risk factors.

-

Yes, ALS is a progressive and fatal disease. The average survival time after diagnosis is 3-5 years, though some people live longer (e.g., 10% survive more than 10 years). Death usually results from respiratory failure due to weakened breathing muscles or complications like aspiration pneumonia.

-

Currently, there is no cure for ALS. Treatments focus on slowing disease progression, managing symptoms, and improving quality of life. Multidisciplinary care involving neurologists, physical therapists, speech therapists, and nutritionists is essential for symptom management.

-

Several medications are approved to slow ALS progression:

Riluzole (Rilutek, Exservan, Tiglutik): Reduces glutamate release, potentially extending survival by 2-3 months.

Edaravone (Radicava): An antioxidant that may slow functional decline, administered via IV or orally.

Sodium phenylbutyrate/Taurursodiol (Relyvrio): Targets cellular stress pathways to protect neurons.

Tofersen (Qalsody): An antisense oligonucleotide for SOD1-mutated ALS, reducing toxic protein levels.

These are often used in combination, along with supportive therapies like ventilators or feeding tubes.

-

Symptom management includes physical therapy to maintain mobility, occupational therapy for daily activities, speech therapy for communication, and nutritional support. Assistive devices like wheelchairs, voice amplifiers, or eye-gaze technology help maintain independence. Palliative care focuses on comfort and quality of life.

-

Ongoing research includes gene therapies, stem cell treatments, neuroprotective agents, and small molecule drugs targeting inflammation, protein aggregation, and mitochondrial function. Clinical trials are exploring combination therapies and biomarkers for earlier diagnosis. Companies like Cortexa Therapeutics are developing innovative small molecules to address underlying mechanisms of ALS, such as those related to neuronal calcium dysregulation.

-

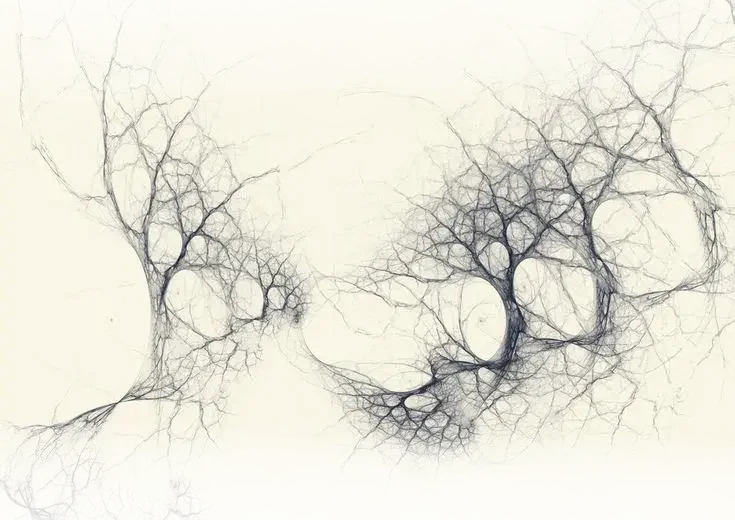

Calcium ions (Ca²⁺) are essential messengers in neurons, involved in synaptic transmission, plasticity, gene expression, and cell survival. They enter cells through channels like voltage-gated or receptor-operated channels, triggering neurotransmitter release and muscle contraction. Mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum help regulate calcium levels to prevent overload.

-

In ALS, motor neurons have limited calcium buffering capacity, making them vulnerable to calcium overload. Mutations in ALS-related proteins (e.g., SOD1, TARDBP) disrupt calcium homeostasis, leading to excessive influx. This activates harmful enzymes (like calpains), causes mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and protein aggregation, accelerating neuron death. Calcium dysregulation is a key factor in ALS pathogenesis and a target for potential therapies.

-

Yes, research suggests that modulating calcium channels or enhancing buffering could protect motor neurons. Calcium channel antagonists or drugs addressing dysregulation show promise in preclinical models, potentially slowing ALS progression by reducing excitotoxicity and mitochondrial damage. Cortexa Therapeutics is exploring small molecule approaches that may help restore calcium balance in neurons affected by ALS.